Life-Space Mapping.

Victor Daniels, Ph.D.

August 2023

Many “inner” conflicts originate in trouble coping with our physical and social environments, yet sometimes the problematical aspects of those environments go unexplored. Gestalt therapists and psychologists from Kurt Lewin to Erving and Miriam Polster and Gary Yontef have noted that “the bad place I’m in” often refers not just to a mental state, but also to the mean streets and the environmental toxins that evoke it or contribute to it. Lewin used the term “life space” for the environments in which we live. These biosocial fields include family, workplace, interpersonal relationships, constructed environments, and natural environments that guide or direct our thoughts and behavior.

Lewin (1890-1947), taught at the University of Berlin until his anti-Nazi stance endangered him and he escaped from Germany in time to avoid imprisonment. In the U.S. he taught at Stanford, Cornell, Iowa, and the Massachussetts Institute of Technology. In addition to extensive Gestalt Therapy training, I studied with two of Lewin’s students, Daniel Adler at San Francisco State University and Harold H. Kelley at UCLA.

Lewin’s equation B = f(P, E) sumarizes his Field Theory, which states that Behavior is a function of the person and the environment.” It reminds us that our individual qualities and the environment interact to cause behavior. The “environmental half” of this statement is often overlooked in psychotherapy. Or minimized. Even Gestalt Therapists sometimes use “field” as consisting of the client, the therapist, the consulting room, and little else. Lewin’s companion concept of the Life-Space reminds us that the “field,” the environmental context within which a person lives includes much than that mini-field. Psychoanalyst and Sociologist Erich Fromm’s later work elaborates this, as does that of Karen Horney.

Gestalt therapy emphasizes here-and-now awareness of one’s personal process. Much of Kurt Lewin’s field theory-based research focused on discovering process dynamics in small groups. Gestalt organizational consulting often includes a consultant walking around observing, listening, and feeling what’s occurring in the various working parts of the organization. In contrast, general systems theory is more analytical, with a well-developed concepts that guide observations and the inferences made from them. This Life-Space Mapping workshop includes all that. It helps a counselor or therapist see and understand the physical, social, and virtual environments in which a client lives out her or his life.

A Life-Space Mapping approach based on Lewin’s work helps a person discover and explore

(1) therapeutic issues,

(2) influences that act on him or her, and

(3) possibilities for change offered by the environment, or available within the environment that he or she may not have realized or considered. This includes physical, social, and natural environments.

It does not take the place of other aspects the Gestalt Therapy process, but complements them. One such session is often enough with a particular client. Exceptions may occur when a client is reticent about disclosing crucial aspects of his or her environment at first, but in later sessions opens up to fuller exploration,

I developed the process described in this workshop for use with college students and counselor trainees. I presented it to the Gestalt community for the first time at the Mexican Gestalt Association’s conference in La Paz in early 2020 in Spanish. It was scheduled for presentation in English at the IAAGT County Clare conference in Ireland in 2022, but I was unable t attend, and presented it in the IAAGT online workship series in 2023.

The rest of this paper, below, consists of the “Cliff’s notes style” notes of the online workshop that I made up so participants wouldn’t feel like they needed to take notes, and therefore could participate fully. Since the number of participants was small, each person went into an online “breakout room” with just one or two other people to do their mapping process. In a training workshop or classroom where we have just one large physical room I usually have participants break into groups of four, working on the floor close to each other with a pile of marking pens in the center and each person with her or his sheet of easel paper extending away from the group. Four seems about right for each person having enough time to describe their map to their companions in the small group. If time is limited or generous, fewer or more might be better.

= = = = =

OUR PROCESS TODAY (instructions for the online workshop)

You’ll have fifteen minutes to draw your present physical life-space. The idea is that a glance at the map embodies the physical space, places, and people in your (someone’s) life. Then you’ll have time to discuss it with a partner, and discuss the partner’s map too. Then you’ll come out of the “breakout room” to the large group where all participants will have a chance to talk. Either beforehand or afterward, Victor will say a few words about Kurt Lewin, the Life Space, and the mapping process

Today: You draw a life-space map of your own.

In your work: Your client draws a life-space map.

Today: You tell another person about what you’ve drawn.

In your work: Client identifies and describes what s/he has drawn

-Today: Your partner reflects and guides you in exploring what the map points to, how it affects you, and what openings or possibilities it offers. Then you do the same thing for him or her. In your work, you guide the client.

-Today: In the group as a whole, either you or your partner describes what happened in your process. Others can question or comment. Then likewise for each other person.

In your work-where you and the client go during the map drawing or after it is up to you and him/her.

After the introduction and instructions are finished, you will go into a virtual breakout room with one or two other people. In this zoom workshop, you each have your own pens and paper. If you didn’t bring them to the workshop, then find some blank paper at least regular letter size (or larger) and half a dozen different marking pens or magic markers if you can). If you don’t have those, I’ll tell you how to make do with plain black or blue pens or pencils.

(If some people go to find pen and paper, we’ll do a 4-minute meditation while they do)

I’ll do an overview run-through of the steps now, and then describe them one-by-one as we go through them. They will also be shown in a window at the right side of your screen.

WHY IS THIS “MAPPING” PROCESS WORTH DOING? BECAUSE IT gives a counselor or therapist a much larger conception of what the client’s life is about than does a traditional intake interview. For example, it

1. Can help identify what Erving Polster calls “neon arrows” of emotional charge or unusual behavior that indicate vitally important directions for therapeutic work. Often a client may not have mentioned one or more of these at all as his or her presenting symptom or problem.

2. Typically reveals many of the principal influences that affect what the client thinks, feels, and does.

3. Often shows who or what is “missing” in the client’s environment. Needed kinds of resources and human and/or other influences that are absent.

4. Can identify valuable resources that are available in the person’s life-environment but are unused or underused, that can serve as a basis for constructive interventions and growth

LIFE-SPACE MAPPING VIRTUAL WORKSHOP SUMMARY

1. WELCOME AND CHECK-IN

2. INTRODUCTION – 10-15 MINUTES (ABOVE() FIND A BREAKOUT PARTNER AND SAY HELLO – 3 MINUTES

4.. DESCRIPTION OF MAP COMPOENTS

5. DEMONSTRATION OF SEVERAL “SAMPLE MAPS” (SEE BELOW)

6. ENTER BREAKOUT ROOMS AND DRAW YOUR MAP AS DESCRIBED BELOW. (SEE DRAW YOUR MAP—INSTRUCTIONS) 15 MINUTES. (expandable to 15 by general request) (In breakout room YOU WILL TALK ONLY TO YOUR PARTNER OR TO VICTOR, who will be available while you’re in the breakout room.)

7. GUIDE YOUR PARTNER IN DESCRIBING HIS OR HER MAP. (SEE INTERVIEW YOUR CLIENT—see INSTRUCTIONS below.) 10 MINUTES (expandable to 15) Note: In a live workshop or therapeutic work this 10-15 minutes would probably take 30 to 60 minutes.

8. REVERSE ROLES. YOUR PARTNER WILL GUIDE YOU IN DESCRIBING YOUR MAP.

9. GROUP YADA YADA YADA.

LIFE-SPACE MAPPING IN-VIVO WORKSHOP, AND INDIVIDUAL SESSIONS SUMMARY, AND EXAMPLES OF PERSONAL MAPS

DETAILS OF “DRAW YOUR MAP”

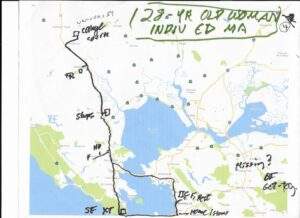

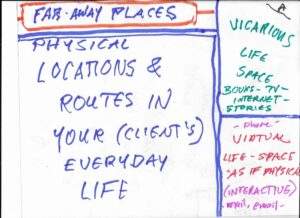

See page “Life-Space Maps 0A.jpg. It’s an attempt to represent the entire life-space. Most of the page is taken up with the person’s present everyday life-space. At the top is space for distant places that are visited occasionally, and also places visited in the past (in dashed lines as on page 0B) that still influence the person’s outlook and feelings. On the right side of the page are spaces for vicarious and virtual life-spaces (see below). Each of these could possibly deserve a page all its own.

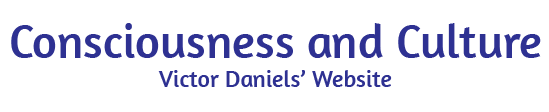

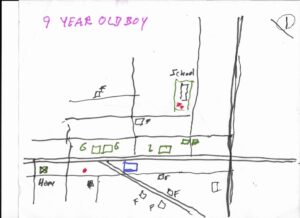

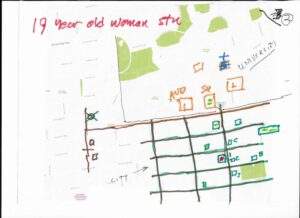

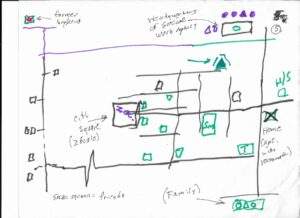

Now that you’ve seen the page 0A overview, you can ignore the top and right hand spaces and use your sheet of easel or butcher paper entirely for your present everyday life space. Pages MAPS 1 through MAPS 5 show example. MAPS 1 shows the life-space of a 9-year old boy. In a town with its center clustered along the main highway and one main business street that angles off it, it shows that most of his daily life-space exists between his house and school. (In exploring the map the counselor or therapist might want to include a request for “scene description” of the interior of the house or school.) MAPS 2 shows the life-space of a young woman attending a big university. The university places where she spends most of her time are orange ssquares. The map is a neat city-street grid of streets on one side of the univrsitity. Green squares are significant places or places with significant people. Her apartment is sown with a red dot. MAPS 3 is of a male student who came for counseling partly because he’s struggling academically at a small university. The map (with railroad tracks at its center) shows part of the small town where the university is located. It shows that a downtown bar and pool hall and the university pizza parlor are where spends a lot of time. (That might be related to the academic underperformance.) MAPS 4 shows the life-space of a female student enrolled in an external degee master’s program that lets her choose professors and classses or related experiences from anywhere in her metropolitan region. Her life-space consists of long freeway routes and off-ramps and places near them.

Finally, MAPS 5 is from a social worker in a small Mexican city who drives to visit clients in several nearby towns. Most of the map is of her own town.

DETAILS OF “INTERVIEW YOUR CLIENT (or “Guide your workshop partner in describing her/his map). The map is a starting point. It shows physical places tham could affect your client. What goes on in them is the main point —and perhaps how their configuration exerts an influence. Think, for example, of the woman with Map 4 who spends most of her time on the freeway. One key to exploring any place on the map is who is there, what are they to the client, and especially what kinds of emotions does s/he feel in their interaction. An empty-chair dialogue can be used with anyone the client mentions.

IN AN INDIVIDUAL SESSION instead of a description or report to others, the therapist or counselor guides the person in an exploration in greater depth. The client draws a Life-Space Map, and describes it to the therapist or counselor. Then the therapist or counselor asks detailed questions about each aspect of the map, with special attention to where there seems to be some emotional charge. As the client tells about the map he or she is repeatedly asked what he or she is feeling, sensing, or thinking at that moment. When the full extent of the map, and the person’s place in it, have been laid out, then the therapeutic or counseling session continues as the practitioner/and or client sees fit.

With MAPS 5, we explored the relationships with everyone portrayed—family, friends, boyfriend, agency supervisor and co-workers, her clients. But there was nothing she in which I sensed one of what Erving Polster calls a “neon arrows” that points to some emotional charge and major personal importance. Then I asked whether there were any people or places she’d left out. Ahhh—far up in one corner of her map was an ex-boyfriend’s apartment that she hadn’t even mentioned. That turned out to be where the work lay, in the unfinished ends of her relationship with him, and complications that involved her new boyfriend.

WHOLE-GROUP DISCUSSION, IN TWO DISTINCT PARTS. COME OUT OF YOUR BREAKOUT ROOM (or your group that was sitting near each other on the floor and using the same pile of pens) INTO THE FULL GROUP.

PART ONE. One person at a time who wishes will share thoughts and/or feelings about the mapping experience. Others may say how they are affected—be brief—just a few sentences unless there is obvious and compelling reason to do otherwise. This is in a “group process mode” rather than an “individual therapy or counseling mode.” In other words, only comments about how you personally are affected by what someone described, from your personal frame of reference, are permitted. No”therapizing.” No intellectualizing. Then another person can share and others may react. In a group of up to about ten, each person can share a few sentences. In a larger group, some can choose to share while others don’t.

PART TWO. Now you can intellectualize, ask questions, suggest possibilities, etc. Especially responses to the question, “”How does this inform my thinking about exile and belonging? GUIDELINES: (1) FOCUS IS ON THE MAPS JUST SHARED. (2) THE ATTITUDE SHOULD BE INQUIRY AND ATTEMPTS TO UNDERSTAND. PLEASE LET GO OF YOUR ATTEMPTS TO LOOK COOL AND SHOW HOW SMART YOU ARE.

A BROADER LIFE-SPACE MAPPING PROCESS..

The maps discussed above are just of the physical places and spaces and people that are a regular part of your everyday life. After using this process once, I realized that we need to include places people only occasionally go, or may have gone in the past but don’t visit any longer. I added another section of the map for these.

After using it a little longer I realized that the “places people go” also included

their vicarious life-space. Where they go reading or media watching. Even where advertising drags their minds.

More recently as the social media age has unfolded, many people now have a virtual life-space that’s not the same as the vicarious life space. It includes interaction with other people on the electronic pathways and places that did not exist before the internet.

Which kinds of virtual and vicarious places do (you) your clients choose to go and spend time in? What feelings or impulses go with those? As with the physical life-space, what are the effects of those choices? What’s missing? Of course, sometimes the line between in-person and vicarious experience may be blurring.

Putting all that together, now you as a therapist have a conception of the mini-universe in which your client exists. It is likely that the one session it takes to gain that will prove valuable in future counseling or therapy sessions.

You might find it useful to pretend that you are a novelist trying to describe the scenes In a client’s life, with the client helping you to do that. You can bring any spot on the map alive by asking such questions as, “In that place, look around. What do you see? Be as specific as you can. What do you hear? What sensations are in your body as you think of yourself there? Are there smells or tastes? Who is there? How do you feel there? What emotions do each person there evoke in you? What do you want to say to anyone? How might they reply? (If there’s energy with that it might be a good spot for an empty-chair dialogue.) This will be easier with some scenes than others—but, try thinking in scenes.

References

References

Ausubel, K. and David W. Orr. (2012) Dreaming the future: Reimagining civilization in the Age of Nature. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green publishing.

Copsey N. & T.L. Bar-Yoseph. (2005) An experiment in community. In Bar-Yoseph Levine, The bridge: dialogues across cultures. Gestalt Institute Press, p. 120-131.

Fromm, E. (1990) The sane society. Henry Holt. Originally Reinhart, 1955.

Lewin, K. (1951) Field theory in social science. New York: Harper.

Luchins, A. S. (1948) “The role of the social field in psychotherapy.” J. Consulting Psychology, 12, pp. 417-425.

Meadows, D.H. (2008) Thinking in systems. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Melnick, J. & E.C. Nevis, eds. Mending the world: social healing interventions by gestalt practitioners worldwide. Santa Cruz, CA: Gestaltpress, 2009.

Murphy, G. (1947) Personality: A biosocial approach to origins and structure. New York: Harper.

Parlett, Malcolm. (2015) Future sense: Five explorations of whole intelligence for a world that’s waking up. Leicestershire, LES, Eng: Matador Books.

Polster, E. & M. (1999) From the radical center: The heart of gestalt therapy. Gestalt Institute of Cleveland Press.

Shiva, Vandana. (1999, 2010, 2016) Staying alive: Women, ecology, and development. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Teachworth, A. & L. Ravich. (2005) “The universal language.” In Bar-Yoseph Levine, The bridge: dialogues across cultures. Gestalt Institute Press, p. 120-131. How does your proposal relate to the theme of Habitat 2020.