George Washington on Political Parties

George Washington refused to join or take part in any political party. He deeply distrusted them. He said explicitly that parties intensify antagonisms and make wise government more difficult. “The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism.” We see that today.

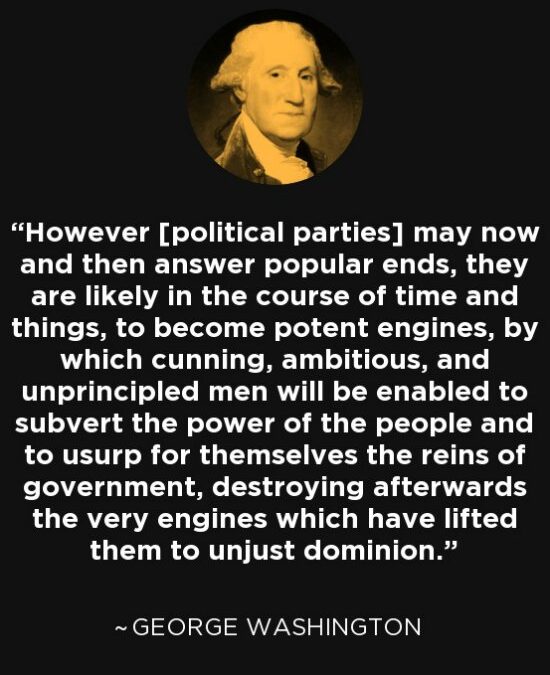

Indeed, George Washington REALLY disliked parties. He wrote, “However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government . . . which have lifted them to unjust dominion. . . The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it. It serves always to distract the public councils, and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another; foments occasionally riot and insurrection, and opens the odor to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government through the channel of party passions.”

When there is an extreme (or in recent years, sometimes even fanatical) commitment to a political party or faction of a party,, its members all too easily forget about justice, decency, reason, humanity, kindness, and the rest of the finer human virtues. They WANT TO WIN AND RULE, and too often all else takes second place.

Even with his comments above, Washington was not finished. He added, “All obstructions to the execution of the laws . . . serve to organize factions, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force. [This puts] in place of the delegated will of the nation, the will of a party, often a small, but artful and enterprising minority of the community; and, according to the will of different parties, to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans, digested by common counsels, and modified by mutual interests.”

We see it all too well today. (We may note that the Constitution says nothing about political parties.) What Washington, Lincoln, and others feared, writes philosopher Jacob Needleman, was “the spirit of party.” This meant the attitude that one’s own faction or part is more important than the whole, or what came to the same thing, and that the best interests of the whole is the same as the interests and program of one’s party. In other words, “We know best, and you shut up and do what we say.” The “spirit of party” meant the commitment to . . . overcome or even destroy, rather than learn from the opposition. (This view, of course, is intimately related to the adversarial structure of our legal system, in which prosecutors and defense attorneys get ahead not by ensuring that the truth is revealed and justice is served but by winning the case, regardless of what happens to be true and just. We saw that writ large when a 5-4 Republican majority of the Supreme Court appointed George W. Bush present rather than letting the votes from a heavily Democratic district, which surely have thrown Florida and the election to Al Gore. We see it now when a 5-4 majority declares that unlimited spending in campaigns by incredible rich people and corporations is the same as free speech. We see it when the same party-line majority maintains that a corporation “is a person.” That’s a bid odd, isn’t it? A tanker car is not a person. A diesel engine is not a person. How than can many tanker cars and many engines that are part of a corporation be a person. Obviously they are not. Obviously the Court is “legislating” for the partisan interests of its party rather than acting with the impartiality that is supposedly a court’s hallmark.

Washington sums up one big reason why such miscarriages of justice occur is rules that govern elections as well as in electoral politics in a sentence: “Few men have the virtue to withstand the highest bidder.” Because recent and present politically partisan Supreme Court majorities ( all of the same party) consistently supports the highest bidder, democracy is gravely endangered.. It is most gravely endangered by the radically ideological partisans of the extreme right who have limitless funds to spend advancing their “spirit of party” rather than the good of the nation. Their habitual practice of blaming “the other” for everything almost always steers us onto the darker path. Hatriots are not patriots, but pseudo-patriots. Patriots have at least some sense of common purpose with their fellow citizens. If you’re inciting people to hate those in the other party, the other race, the other country, you can sing the anthem as loud as you like and wrap yourself in the flag so tightly that you can’t see out, but you’re no patriot.

Historian James Thomas Flexner tells us that Washington “deplored the adversary theory which sees government as a tug of war between the holders of opposite views, one side eventually vanquishing the other. Washington saw the national capital as a place where men came together not to tussle but to reconcile disagreements. . . . Washington’s own greatest mental gift was to be able to bore down through partial arguments to the fundamental principles on which everyone could agree.” George Washington’s democracy, says Jacob Needleman, “is not the freedom to try to destroy each other physically or philosophically or morally, but the freedom to bring one’s own best thought together with one’s best effort to listen and attend to the other. ‘The aim is not to reach the pale and crooked version of mutual accommodation that we call “compromise’ . . . but to discover a more comprehensive intelligence that allows each part and each partial truth to take its proper and necessary place in the life of the whole. . . .To have unity. . . one must struggle to become free from the false . . . separation that is represented by what we are referring to as the spirit of party.”

Former Vice President Walter Mondale recalls that when he served in the Senate in the 1970s, “debates were always heated. But I don’t think they had the kind of nastiness they do today. We need to lighten it up . . . to find a way of talking with each other. I’ve won and I’ve lost. And I like winning better. [But] when you run for office in a democracy . . . one person wins and one person loses. I think it’s important that we do it with civility, with respect.”

We would be a better, more decent, stronger nation by returning to George Washington’s view of democratic discourse. And by each thinking for ourselves rather than parroting the beliefs and attitudes that our party bosses or our friends or family members who are ideological zombies lost in Zombie-land want us to accept.

BARRY GOLDWATER said, “A lot of so-called conservatives think I’ve turned liberal because I believe a woman has a right to an abortion. That’s a decision that’s up to a pregnant woman, not up to the pope or some do-gooders on the religious right.”

BARRY GOLDWATER said, “A lot of so-called conservatives think I’ve turned liberal because I believe a woman has a right to an abortion. That’s a decision that’s up to a pregnant woman, not up to the pope or some do-gooders on the religious right.”