Concentrative, Contemplative, Meditation, Mindfulness, Spirit, Women & Gender

The full answer may be longer than you wanted.

There are at least four different basic answers—and then there’s all the rest of it.

One basic answer is, “Whatever position gives you the best signal that your mind has gone away from awareness-in-the-moment into either drifty mind or washing-machine mind,

A second is, “a classical cross-legged or chair position with a mudra of your choice.”

A third is, “Any position that you can physically manage and maintain for some time.”

A fourth is, “Any position in which you’re willing to meditate, in contrast to other supposedly correct positions that cause you to avoid meditating when you think about them.

Any one of these answers might be best for you. You can judge that for yourself after reading about each.

The first answer contains the key insight that the mental effort required to stay aware of your posture in the present instant is itself a powerful aid to maintaining a focused meditative state. Sitting straight upright on either a cushion or chair, with your eyes focused slightly downward anywhere from about six feet ahead to the far horizon, and your hands forming a perfect (i.e. non-drooping) mudra is best of all if you can manage it. (Yes, that’s the second answer above.) Why? Because your mind will inevitably have a tendency to drift here or there, and if you’re sitting in such a position with the intention to maintain it, then as soon as you notice that you’re slumping just a bit, or that in your Zen mudra your thumbs are pointing downward rather than forming an egg than a round ball, or that your jnana mudra is similarly droopy, you can straighten up your back, reform your mudra, breathe deeply, and continue your classical meditative posture. Maintaining it requires mindful attention to keeping some of your mind in the present.

If, of course, you’re doing an extended meditation—especially in a group—in which you’re supposed to remain motionless, after a time your body will be experiencing physical pain just from maintaining the fixed position and you will have no alternative but to be aware of your physical position and sensations. When you see a picture of a group of people meditating, all sitting in the very same or almost the very same posture, that’s probably what’s happening. There’s a special kind of psycho-somatic learning that’s occurring just by maintaining that position. (In many meditation groups, after such a period of sitting there’s a period of walking meditation that gives your body a chance to move.

With the second answer above, a full-lotus meditation is favored by some practitioners. That’s a cross-legged position with each leg crossed above the other and the soles facing upward. (See the link below.) Some yogis maintain the ability to sit full-lotus, or in even more demanding and in some cases amazing positions, into old age. Those who do usually sit (or in some cases stand) in such positions every day. When I was in my twenties and thirties I used to sit full lotus. Toward the end of my thirties a doctor told me, “There seems to be some evidence that full lotus is bad for your ankles, at least for some people.) After that I moved to a half-lotus position in which the legs are crossed only one is pulled up through the other. Less demanding yet is a simple cross-legged position. Your body will probably tell you which cross-legged position can work for you.

In any position on the floor or ground it helps to raise your butt about four inches off the floor so that there’s a downward tilt from your butt to your knees. Every meditation center has cushions that do this. It’s best to sit on the forward edge of the cushion rather than in the middle of it. The downward slope makes it much easier to keep your spine straight and sit up straight. And it’s more comfortable than sitting flat on the floor or ground. Most pillows doubled once will do nicely as a substitute for a meditation cushion—but if you want the real thing you can find them in shops that have meditation accessories and online. When i’ve had neither cushion nor pillow, I’ve found that turning one clean sandal or shoe upside down, placing it on top of the other, and using the two as a cushion usually does the job. Outdoors you might find a small slope or bump somewhere nearby that’s about the right size to raise your butt enough for comfortable sitting and a straight spine,

There is also kneeling meditation, kneeling with your legs together and back straight up. Many people who favor that position find that a cushion or pillow (or even a folded jacket or sweater) between butt and legs is useful.

In meditation halls I sometimes noticed some of people sitting up straight in chairs rather than on the ground or a cushion in a cross-legged position. In most places there were a few chairs somewhere in the room, mostly occupied by elderly meditators. An older friend and I sometimes led workshops together and he always sat in a chair. “My knees just won’t go into a cross-legged position,” he said. Now I’m older myself, with arthritis in my joints. At some point I moved from usually sitting cross-legged to preferring the chair. Still with a straight spine, looking slightly downward, keeping my mudra in its proper position, but my legs said “Thank you for not making us sit cross-legged on the ground any more.” My chair position is sometimes with my legs straight down and sometimes with them cross-legged beneath me on the chair.

All that involves sitting. Some years ago when I was doing a weekly class I asked the students to keep a meditation journal. To write down just a few sentences about what happened during their meditation period each day. One young woman consistently wrote that she just didn’t feel called to sit up during her meditation but preferred to lie down. She did, however, keep one of the most detailed and best journals of her meditation experience, and said it was almost always valuable in helping her feel better. As you probably know, lying down tends to predispose people more toward a hypnogogic, dreamlike state and less toward a mindful, moment-by-moment awareness state. Her meditations were a kind of combination of both. And very interesting, especially in their contemplative excursions. That was what worked for her. It was a clear case of meditating in her own way or not at all. So that becomes my final statement. Lying down meditation is not a position I suggest, but better than none. There are, after all, statues of reclining Buddhas scattered all over Southeast Asia. And it just might be what you need at a given moment. Assess your needs and learn to trust yourself.

If you want to meditate standing up, such as while waiting for a bus, I recommend a moving meditation rather than standing motionless. An online search for <standing moving meditations> will bring up a number of YouTube videos of such movement patterns. The ultimate expression of this is Tai Chi.

When properly performed, hatha yoga is also a meditation. Attention to your breathing in a meditative manner while performing your asanas, and to fully experiencing the sensations of your body as you move and the rest of your field of awareness make your yoga session into a transformation in consciousness that’s quite different than it is if you go through the motions with an athletic mindset. This can be structured pranayama or simply bare attention as described just above,

For photos of eight sitting meditation positions see Melissa Eisler’s <https://mindfulminutes.com/how-to-sit-for-meditation/>.

Concentrative, Cultures, Meditation, Mindfulness

INDIA NAMES, CHINA COUNTS: OF MANTRAS AND COUNTING MEDITATIONS

Most of the effective ways to meditate include some way to maintain a focus on your breathing. Why? Because it’s a way to stay aware of what you’re thinking, feeling, sensing, and/or doing rather than being completely identified with your action or experience. And that’s part of the essence of meditation—being aware, moment by moment, of what you’re doing rather than being completely caught up in it.

The two most popular ways to stay aware of your breathing—which in turn helps you stay aware of whatever else you’re doing—are mantras and breath counting. A mantra is most effectively used when silently repeated in rhythm with your breathing. For example, silently speaking the mantra on your inhalation and noticing whatever else you’re aware of during that in-breath and then emptying both the mantra and everything else out of your mind on the outbreath.

Breath counting is similar. Count one number on the in-breath and notice whatever else you’ve become aware of (thinking, feeling, sensing, and/or doing if you’re not sitting silently while you meditate. Then empty the number and everything else out of your mind on the outbreath.

There’s more to it than just described with both mantras and breath-counting, and we’ll come back to that “other” in just a minute. But first, an adventurous little journey to India and China. In India we find that people name the days and months just as in most of the West. “Sunday, Monday (think Moon Day), Tuesday, . . . etc.” Likewise with months of the year: January, February, etc.. Just like in the rest of the Indo-European language family. Now let’s jump over to China. Those names are nowhere to be found! Instead the days and months are counted. The days of the week are called Day One, Day Two, Day Three—and so on. And the months? Well of course, they’re Month One, Month Two, Month Three—right on up to Month Twelve. (Could that constant counting in everyday conversation have something to do with why many Chinese seem to be so good at math? Or maybe it’s the other way around—that mathematical aptitude is why they count the days and months instead of naming them. All just guesses.

In Japan, just for the record, the days are named after elements rather than planets as in the West. Except Monday, which is the day of the moon there too. Tuesday is the day of fire, Wednesday of water, Thursday of wood, and Friday of—yes–gold! Saturday is the day of earth. As for the months—well, there it gets a little complicated. In modern Japanese they’re counted, just as in China. But in the old days they had names. Sometimes the old names are still used in poems and novels.

At this point your inquisitive mind probably wonders, “What about Southeast Asia, which is sort of between India and China?”

Moving your token to Thailand, you’ll find that the days of the week are named after astrological signs from India and Sanskrit. But in Vietnam, closer to China, they count them.

But if you really want everything turned on its head, in English we count the years but in China they have names for them. As the Japanese would say, “Ah, so!”

Now, back to the question, “What does all that have to do with meditation?”

The short answer is that breath counting is more popular in China and Japan while mantra meditation is more popular in India. Almost all are derived from the ancient Sanskrit language, which intriguingly enough has a far more extensive vocabulary for diverse personal qualities, states of consciousness, and “higher” states of consciousness than any contemporary language. (Does that suggest highly developed ancient civilizations, such as the “mythical” Atlantis and Lemuria? How else would such a language come into being?) A mantra has the advantage that anyone can learn it. And each mantra has some specific meaning that can influence a person’s attitude and outlook when repeated over and over again for a long period. If there’s a particular quality you want to develop, that feature of mantras can be useful. Some gurus and traditions assign mantras to those who come to them for meditation instruction—and in some cases, that’s your mantra forever! Other traditions allow people to choose their own mantra and to change it when they want to work on developing a new and different personal quality. Kooch N. Daniels and I offer a page of useful mantras in Matrix Meditations (available either in paperback or as an e-book.) If that’s not enough for you to choose from or you don’t want to shell out $13.99 for our amazing and wonderful book you can do an online search for “Sanskrit words” and you’ll find many different sites that offer such terms absolutely free! (but some—not all—will try to sell you all sorts of other things.)

It’s a little easier to maintain your mindful presence and with breath-counting than mantra meditation, but it doesn’t have the same feature of mentally reinforcing some particular quality. Nonetheless, some advanced yogic traditions in India, such as Kriya yoga, favor breath counting. There are beginning breath-counting methods that are almost as easy to do as mantra meditation and advanced methods that require great attentiveness and can develop a high degree of mental discipline.

The one thing that the most effective mantra meditations and both beginning and advanced breath counting meditations have in common is a focus on breathing. Each adds something extra to the most basic breathing meditation of all, which is to do no more than notice and sense as you breathe in and breathe out. In that most basic practice, as soon as you realize that your mind has drifted off to thinking about something—anything—else, then just bring your attention back to noticing breathing in, breathing out, breathing in, breathing out, and no more.

What can be simpler? Or easier? Sound like child’s play, doesn’t it? Why bother with anything else?

Because actually it’s incredibly difficult to keep your attention focused on your breathing and nothing else. (If you don’t believe it, try it for two minutes right now. See?) The washing machine of our mind craves to swish all the zillions of thoughts it contains back and forth and all around—and what was that about breathing? I forget. . . “

That’s why even a basic mantra or breath count with your breathing is useful. It gives you something to hang onto when the storm winds of your mind or emotions want to blow your attention away. More about each of them in exciting future blogs.

How simple or how complex a practice suits you depends on the character of your own everyday ordinary waking consciousness. Some people who have a stoic temperament find that a fairly simple and basic practice is perfect for them. Others who have more of a “monkey mind” that tends to jump all over the place find that a more complex and demanding practice does a better job of helping them focus and stay present, paradoxical as that may sound. More –much more– about both simpler and more complex ways to meditate in other blogs. (Or get them all at one time in one place in the convenient, well organized, beautifully written book mentioned above. )

In the meantime, if you do nothing else, at least tune into your sensations of breathing in, breathing out, breathing in, breathing out —like a swinging door—when you have nothing else to do!

Ciao Bello. Or Ciao Bella, as the case may be. Victor

Concentrative, Counseling & Psychotherapy, Everyday Awareness, Meditation, Mindfulness, Psychology

If you’d like a 3-minute mini-meditation available to use when you’re distressed, upset, emotionally off balance , here it is. It’s almost as simple as a meditation gets, because that’s about all a person can handle when they’re in an emotional meltdown. When you’re really flustered, a basic railing to grab onto is what you need, because you probably can’t focus on much more than that.

If you’re with someone else who’s freaking out and you want to help, you can talk them through this same process described just below. Speak out loud, almost verbatim as written below, making whatever tweaks fit the situation. Make sure your tone of voice is calm and soothing, It might or might not be appropriate to hold the person’s hand to help ground them. You can check that out by touching their hand lightly and seeing whether they take hold of it. Respect that message.

No frills. So this is for you when you’re upset. Or for you to use to help someone else when they’re upset. If you’re a helping another person at a fire, an accident, a crime scene, or any other crisis situation –or even a situation that’s an emotional crisis even if someone else wouldn’t think the situation itself is a crisis–this can prove useful.

STEP ONE

If you can, sit up straight. If not, sit or lie however you need to.

Notice your breathing. If it’s slow, that’s fine. If its fast and shallow, slow it down. At least a little slower and deeper.

STEP TWO

Now, as you inhale, count the number “1.” Hear it in your ears if you can. If your eyes are closed, try to visualize i|T.

As you exhale, notice everything you’re seeing and hearing in your mind, and let it all flow away on your outgoing breath as completely as you can

Now as you inhale again, count the number “2.” Concentrate on ‘hearing’ or visualizing that number as fully as possible. If you can’t do either, just ‘think it.

As you exhale, again notice what’s filling your mind, and again let it flow and blow away, so that when you’ve exhaled completely your mind is as empty as possible.

STEP THREE

As you inhale again, mentally count the number “3.” When you’ve inhaled completely, take an instant to notice

anywhere your body feels tense and tight.

As you exhale, let yourself release and let go of that tension at the same time that you’re letting go of any ideas that

have formed in your mind.

STEP FOUR

For your next seven breaths, do just as you did with number 3. With each breath, change the number to the next higher one (this helps keep your focus on what you’re doing rather than letting your mind run away to think about whatever was disturbing you). On the incoming breath, silently recite the number and notice whatever else is coming through your mind—or even spinning around in it. Then on the outgoing breath, focus your attention on noticing any physical tension or tightness anywhere in your muscles and letting go of it—while at the same time letting go of whatever other words or sentences or imagery are coming through your mind. You’re letting go of words, letting go of imagery, letting go of muscular tension and tightness. It’s like that old song —all those thoughts and imagery and muscular tensions that are bothering you are singing “Please release me, let me go!” to you.

If you’re guiding another person through this process, verbally walk them through breaths 4 through 10 just as you did with breath 3.

After just these 10 slow breaths you’ll probably find that you feel much better than you did—even though this may take you only 3 or 4 minutes. If you (or the person you’re helping) are still quite upset, then use the process again with the next 10 breaths, using the releasing physical tension process you began with breath 3 in all ten breaths.

The key insight with this process is that the mind-body connection works in both directions. When you’re upset, you tense up your body—automatically. To become less upset, as you relax your body consciously, in turn it relaxes your mind.

© 2021 by Victor Daniels.

You’re welcome to share this with whomever you wish so long as no charge or profit is made from doing so. Inclusion in any electronic or hardcopy post or document for which a charge is made requires consent of the author.

Concentrative, Meditation, Mindfulness, Spirit, Uncategorized

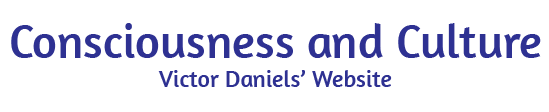

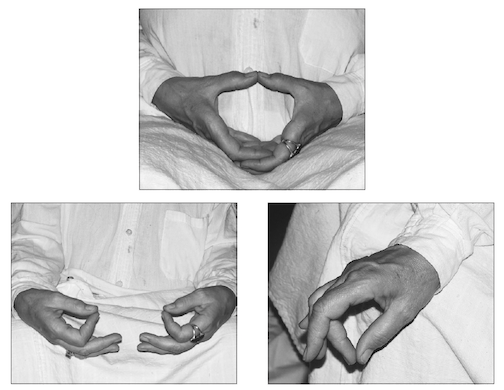

MUDRAS AND MOVING MUDRAS

This is small yet useful way to help maintain focus of your attention while you meditate. It can help you keep your mind from rambling around when that’s not what you want to do. It’s an alternative to the “visual splitting” described in another blog. Actually this is simpler and more basic.

A mudra is a hand position of a kind used by both Budhist and Hindu meditators. The position of palms together and fingers pointing upward used in Christian prayers and also those of many other spiritual traditions is a mudra. Its meaning is a communication with the divine (which might or might not actually happen, depending on your state of consciousness.) This prayer mudra is called the atmanjali. In some cultures it’s also used as a sign of respect or gratitude —especially Japan and India.

Another popular mudra is the jnana mudra that symbolizes opening the heart to the wisdom of heaven. You’ve probably seen a statue of the Buddha sitting cross-legged with his palms turned skyward on his legs and the thumb and index finger of each hand touching. Or you can use the thumb and middle finger.

If you’re in public and you want to meditate without looking obvious you can turn the jnana mudra upside down as shown in the third of the three pictures with this blog. Long ago I started sometimes doing that after I was using the jnana mudra while sitting against a pillar meditating as I waited for a train in a crowded railway station waiting room in which all the seats were gone. I didn’t want to move until my meditation was finished.Some people thought I was begging and dropped coins into my hand. After that I started turning the jnana mudra upside down in public. I call that the invisible mudra. All others can see is your knuckles.

There are many mudras. You can find entire books about them. These three are enough for me.

Maintaining a mudra can help keep a clear centered mental state. In the Zen tradition if your thumbs droops instead of keeping your mudra almost circular it’s a sure sign that your mind has wandered.

For me with my typically busy mind a mudra wasn’t enough. I could maintain one while my mind wandered. Eventually I realized that I could pair a slight movement of my mudra with my breathing. That is, move my thumb and finger apart slightly (or in the Zen mudra my two thumbs apart) as I breathed in and then let them touch again as I breathed out. And so on over and over.

What’s happening there? With more of my mind anchored in paying attention to my meditative practice, less of my attention is available to go wandering. It works for me.

But it might not work for you. Try it and see. If it does, great! If not, if you find the slight separation and touching in rhythm with your breathing distracting rather than helpful after you’ve tried it for a couple of weeks, you can use a mudra with no movement instead. I suggest at least that.

Unless you don’t need it at all. Some people (but not many) can fairly easily keep their mind focused in present awareness of just one thing, such as their breathing. Pure mindfulness.

If that’s not you, then a basic nonmoving mudra may serve you well. If you try that and your mind still jumps around a bit, then a moving mudra may be just right for you.

If even that isn’t enough — if you’re one of those people with a mind that tends to dance around everywhere (like me) then you can try using both a moving mudra and visual splitting together. Doing that is a complex enough task that it leaves less of your attention available to go wandering. It anchors more of it in the here-and-now. Or in closely focused contemplation, if that’s what you want to do.

(photo with this blog is from Matrix Meditations by Victor and Kooch N. Daniels, available as both an e-book and hardcopy.)

© 2021 by Victor Daniels.

You are welcome to share this with whomever you wish so long as no charge or profit is made from doing so. Inclusion in any electronic or hardcopy post or document for which a charge is made requires consent of the author.

Concentrative, Meditation, Spirit

MEDITATION — THE ESSENCE

Basic Meditation Instructions, Part II

CONCENTRATIVE MEDITATION

Concentrative meditation develops your ability to know what you are doing with your attention at any given moment and to focus your attention (and often that of others with whom you are conversing) where you wish. This ability has been shown to be useful in diverse areas of life. It is also essential to witness consciousness or mindfulness meditation, which will be described in Part III. Two different forms are described here, and you can choose the one you prefer or use them both at different times.

Counting style. Choose any object to focus your eyes on. As you did just above, count from one to ten. This time silently count one number on each incoming breath, from one to ten. Then count the same number ten times on each outgoing breath. Like this: 1-1, 2-1, 3-1, etc. up to 10-1. Then take a single breath in which you do not count. Then count a second sequence of ten, like this: 1-2, 2-2, 3-2, etc. up to 10-2. Another empty breath, then ten breaths with the number 3 on your exhalation, etc. Ideally you will do this for 110 breaths, up to 10-10. Then do ten more snapshot breaths to end your session. Whenever you lose count, continue from the last pair of numbers you can remember clearly. If you don’t have time or don’t want to count up to 10-10, stop whenever you wish and end your session with ten snapshot breaths.

On each outbreath, notice all the chatter and images that have formed themselves in your mind and imagine them flowing out of you and away as you exhale, leaving your mind calmer and clearer. Whenever you notice that you have forgotten your counting or you are no longer looking at the object you chose for your visual focus, first notice where your mind has gone in case it’s to something important you need to remember (you might want to keep a pad and pen to jot down a word or two as a reminder when things occur to you.) Then gently move your mind back to your counting. Don’t try to keep things out of your mind – just bring your mind back to your counting, again and again if needed.

Mantra style. Select a mantra that feels agreeable and useful to you. You can find one by looking at the index at this link, or by doing a web search for “Sanskrit words” or “mantras.” Or even choose a word or phrase in your native language that refers to a quality you want to cultivate. Just as with the counting above, choose an object for your visual focus. On each inhalation, silently repeat your mantra to yourself. On each exhalation, you can either (1) count the same number for ten numbers as described just above, and then move to a second number for the next set of ten breaths, or (2) just repeat the mantra on your inhalation and let your mind go silent on the exhalation, allowing the thoughts that have formed themselves to flow away. When you notice that you are no longer repeating your mantra, return your thoughts to it. DO NOT, however, use repetition of the mantra to try to “push” other thoughts, feelings, or sensations out of your mind. You could end up pushing out things you very much need to notice or hear. Just notice where your mind has gone, jot down a reminder of that if it’s important and you wish to, then bring your attention back to your mantra. Here too, ten snapshot breaths are a good way to end your session.

OR, you can regard the starting sequence and a period of concentrative meditation as the first two stages of your sitting, and then go on to mindfulness / witness consciousness meditation or to a contemplative meditation.

Part I of this series of five mini-articles offered an introduction to what meditation can do for you and presented a useful meditation “starting sequence.”

Part II describes concentrative meditation.

Part III will describe witness consciousness (yogic term) and mindfulness meditation (Buddhist term) and They overlap considerably but not totally.

Part IV will describe contemplative meditation. (not yet posted)

Part V will be on everyday awareness practices. (not yet posted)

All this is just “the essence.” If you’d like this and many advanced practices all in one handy place, you will enjoy Matrix Meditations, by Victor Daniels and Kooch N. Daniels. Click on the cover to go to the book’s home page. You can get the e-book for under $13.99, and used copies online for little more than postage. Of course, a brand-new paperback copy (from your local bookstore or another online vendor) is a treasure.

Matrix Meditations